Sometimes life hands you lemons; sometimes life hands you a rare genetic disorder that derails your military career. Rachel Astete Vasquez, American Water Works Association’s 2019 Woodard & Curran Scholarship recipient, was handed the latter. Instead of making lemonade, she’s pursuing a Ph.D. in environmental engineering and researching more sustainable ways to dispose of human waste.

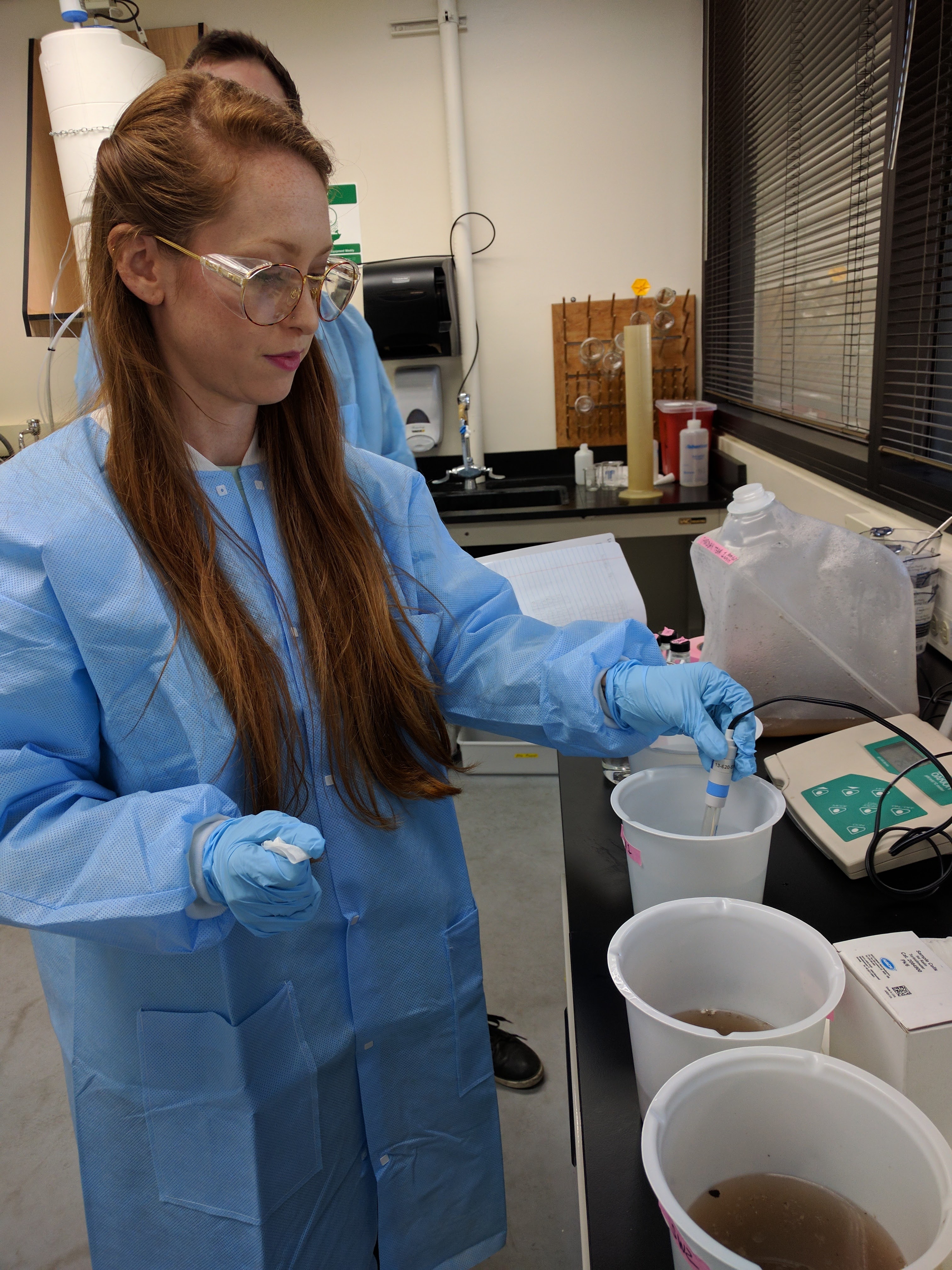

Rachel is enrolled in a joint doctoral program between San Diego State University and University of California San Diego. Her Ph.D. research focuses on a waterless flushing toilet, currently in use in Botswana where it improves sanitation in areas where there is no access to water lines.

Rachel is enrolled in a joint doctoral program between San Diego State University and University of California San Diego. Her Ph.D. research focuses on a waterless flushing toilet, currently in use in Botswana where it improves sanitation in areas where there is no access to water lines.

“This toilet flushes by way of a self-contained plunging mechanism that pulls excreta into the tank below, meaning you don’t have to run potable water to it in order to flush feces away,” she explains. “The tank has an anaerobic digester with an agitator, and the waste then moves to a biofilter — basically what’s contained in a septic tank.

“We use a lot of drinking water to flush toilets in the U.S. and other developed nations, which is a luxury we take for granted,” she continues. “I’ll be expanding on the existing design and seeking knowledge for ways that this kind of toilet can be used here.” The existing toilet’s main obstacle for use in the U.S., she says, is its effluent. Containing small amounts of pathogens and high nutrient levels, the toilet’s end product poses health and regulatory compliance issues that make it not yet suitable for mass adoption here. If Rachel and her team can mitigate these problems, she says the waterless toilet would be not only a sustainable choice for homes and businesses, but a great sanitation solution for places where it is not feasible to run potable water out or sewage back, such as homeless encampments and national parks.

Why Toilets?

Rachel has been passionate about the environment for a long time, but it wasn’t until she had already started her bachelor’s degree that she found her way to environmental engineering. “I chose electrical engineering at first because I wanted to do something with solar power, but found that environmental engineering suited me better,” she says. She got into waterless toilets during her pursuit for a research topic to cover during her graduate studies.

“I didn’t have a basis for my potential thesis at the time, and my adviser started telling me about this waterless toilet that she encountered in a rural area of Botswana, and mentioned that it would be a great opportunity for a student to explore its components and improve it to be used more widely throughout the world,” Rachel explains. “I’ve taken it from there, coming up with ideas for what we can explore and how we can improve its use.”

As she was continuing to develop ideas for what she would cover through her research, she began to worry that the timeline for master’s degree would be too short. “I had all these questions I wanted to answer through my research,” she explains. “I felt like I couldn’t get it all done in the two years of my Master’s. A lot of people doing this kind of work pass the project along to someone else when they complete their degree, but the idea of that was heartbreaking to me. When I spoke to my advisor, she said, ‘Go for your Ph.D. and you can cover more questions,’ so I did.”

An Unusual Path to the Ph.D.

Rachel’s career path has been out of the ordinary, to say the least. After high school, she left home to begin a career in the military. “For some people, they make a four-year commitment and then they’re out,” she says. “For me, this was a long-term career choice; it’s what I wanted to do until I retired. I think that made it all the more challenging, when only 1/3 of the way into my contract, I was thrust out due to medical issues.”

Prior to her service, Rachel says she had no symptoms. Trouble began aboard a naval ship traveling the South Pacific. “I made it as far as Guam,” she recalls. “On the legs between California and Hawaii, and Hawaii to Guam, my hips and shoulders kept dislocating — not totally popping out to the point where I needed a doctor to put them back in, but it was very painful. And it was happening to me every day. A small ship rocking hard on the ocean was a bad place for me to be.”

She was diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), a genetic condition impacting the skin, joints, and blood vessels. EDS affects an estimated 1 in 5,000 people, with its most common symptom being hypermobility in joints. The constant hyperflexion and dislocation take a serious toll on connective tissue, which results in chronic pain, muscle weakness and worse. In addition to stripping Rachel of her comfort and mobility, EDS abruptly ended her military career.

“It felt like it came out of nowhere,” she says. “I had gone from being completely physically capable, to being totally broken down, only able to walk from the handicap spot to the building; being wheeled into the hospital. On top of that, there was a lot of judgment — EDS is an invisible disability, and people make a lot of assumptions when they see a young person parking in a handicapped spot. A lot of the people I had known in the military thought I was making it all up. It made my transition to civilian life even harder while facing this big question of what I would do next.”

With the help of good doctors and a supportive husband — who at one point was called home from his own deployment to care for her, Rachel is in much better shape these days. While EDS has no cure, medical treatment and lifestyle changes have made it possible to manage. The condition still causes pain and saps her energy, but that hasn’t stopped her from rising to meet and beat every challenge academia has thrown her way.

Checking Boxes and Taking Names

Rachel’s achievements have come largely through her own appetite for a challenge. She knew engineering could be a tough field. She knew that the factors that make her different from traditional students could be tempting rationalizations for coming up short. However, if it’s not obvious by now, Rachel has no love for excuses.

“I check a lot of boxes,” she laughs. “I’m a disabled veteran; I’m a woman; I’m Hispanic — my father immigrated from Peru and didn’t become a citizen until I was 14; and I’m the first person in my family to go to college. But I don’t feel limited by my identity. If anything, I find it empowering that I’ve made it this far despite the challenges I’ve faced.”

Her advice for others who check the boxes not traditionally associated with success in the STEM fields: “Make your accomplishments the meat of who you are. There are so many things I am in contrast to other people, but it’s a part of the whole — not what’s going to make you amazing. Everyone’s goal is to be something of importance, someone who matters and makes a difference. You can do it. Your abilities are not defined by your obstacles or what boxes of diversity you hit. For some of us it takes more work, but no one should think they’re not smart enough to do this work or worthy of these experiences. Reach out for help if you need it and keep going.”